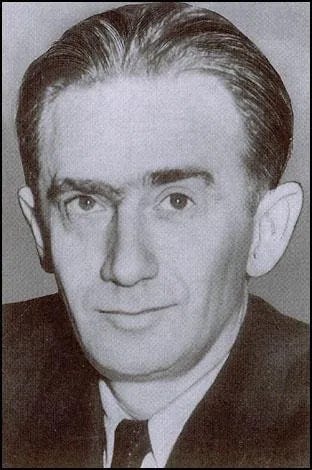

Walter Krivitsky - CODENAME - WALTER

Born Samuel Ginsberg...Was he suicided?

Walter Krivitsky, born Samuel Ginsberg in 1899, was a Soviet military intelligence officer who defected to the West in 1937, becoming a prominent critic of Stalinist Russia. His life, riddled with aliases and secrets, provides a fascinating case study of early 20th-century geopolitics and the tradecraft of Soviet espionage. This post explores Krivitsky's journey, his methods, and the controversies surrounding his life and death.

Early Life and Revolutionary Beginnings

Krivitsky's early life was steeped in the political and social unrest of the Russo-Polish border region. Born into a Jewish family in Podwołoczyska, Galicia (present-day Ukraine), he joined a radical youth movement at the age of thirteen. He later recalled how "the plaintive melodies of my suffering race mingled with new songs of freedom". This early exposure to revolutionary ideals shaped his trajectory. By 1917, at the age of eighteen, Krivitsky embraced the Bolshevik Revolution, seeing it as a solution to poverty, inequality, and injustice, and joined the Bolshevik Party with his "whole soul". He adopted the pseudonym "Walter Krivitsky," a name with Slavic undertones meaning "crooked" or "twisted," hinting at his future path. He fought in the revolutionary army of the Ukraine during the Civil War.

Rise Through the Ranks of Soviet Intelligence

Krivitsky's career in Soviet intelligence began in 1922 when he was sent to Poland as a military intelligence officer. He quickly rose through the ranks, becoming a brigade commander, a position equivalent to an American brigadier general. He traveled extensively between Moscow, Paris, Vienna, Berlin, Rome, and Holland, earning the Order of the Red Banner for his efforts.

Early Operations: Krivitsky's work involved undermining the war efforts of perceived enemies. He organized strikes in Danzig and other locations to stop arms shipments, and worked to disrupt communications and sabotage infrastructure. For instance, he organized a successful railroad strike in the Czech railroad junction of Oderberg, persuading the Czech trainmen to walk out rather than handle Skoda munitions for the Poland of Joseph Pilsudski. He also wrote leaflets urging railroad workers not to transport weapons that would be used to kill their "Russian working-class brothers".

Counterfeit Currency Scheme: In 1929, Krivitsky became involved in a plan to obtain foreign currency and undermine capitalism. The operation involved the creation of counterfeit $100 United States Federal Reserve banknotes. These bills were printed with meticulous detail, including individual serial numbers. Krivitsky's role included using the counterfeit currency in casinos, buying chips, and then cashing in the remaining chips for real bills.

Military Intelligence and NKVD: Krivitsky worked for both the Red Army’s Fourth Bureau (military intelligence) and the NKVD, with each agency considering itself superior to the other. According to a defector, the NKVD was short of capable agents and eager to recruit away those from military intelligence. The military was more secretive and unknown to the public both inside and outside the country.

Chief of Soviet Military Intelligence: In July 1933, Krivitsky was transferred to Rotterdam, becoming the director of intelligence with liaison responsibilities for other European countries. He was now "Chief of the Soviet Military Intelligence for Western Europe". He used the cover of a quiet Austrian art dealer, operating an antique shop in The Hague. This allowed him to travel and live with his wife, a practice that the NKVD realized made a good cover for espionage activities.

Tradecraft: Techniques of a Soviet Spy

Krivitsky's success as a Soviet spy was rooted in his mastery of tradecraft. Some key aspects of his operations included:

Building Spy Networks: Krivitsky established spy networks across Europe, recruiting individuals from various backgrounds such as journalists, politicians, artists, and government officials. Some of these agents were motivated by financial gain, while others were ideologically driven communists. One of his most important agents was Pierre Cot, the Air Minister in the government of Léon Blum.

"Borrowing" Documents: Military Intelligence officers were trained in the use of Lecia cameras. Instead of stealing documents outright, they would borrow them long enough to photograph them before returning them to their original locations. This tactic minimized risk and prevented the loss of important information. Krivitsky would handwrite his reports, photograph them, and send the undeveloped film to Moscow through the embassy using special mailing canisters that would self-destruct if opened improperly.

Use of Passports: Krivitsky confirmed the use of passports from deceased individuals. He saw a batch of about a hundred passports, half of them American, in the offices of the Foreign Division of the OGPU. After investigating the family histories of the original owners, these passports were adapted for use by Soviet agents.

Cover Identities: Krivitsky lived under various aliases and maintained multiple residences. In The Hague, he used the identity of Dr. Martin Lessner, who sold art books. He was also known as "Walter Thomas", "Walter Poref", and "Schoenborn". His ability to seamlessly switch between different roles and identities was a critical component of his espionage activities.

Recruitment of Agents: Krivitsky recruited Hans Brusse, who served as his chauffeur, aide, and special assignment operative. Brusse was also described as an expert locksmith. Another important agent was Henri Pieck, an artist who posed as a Dutch businessman in Leipzig and met with Ernest Holloway Oldham, who headed the department that distributed coded diplomatic telegrams at the Foreign Office.

Exploiting Personal Weaknesses: Krivitsky's network exploited personal weaknesses, as seen in the case of Oldham, who was described as having "a riot of drunkenness, alcohol-related sickness, professional sloppiness, wife beating, unaccountable spending and insubordination". This behavior made him vulnerable to recruitment and exploitation.

Defection and Anti-Stalinist Activism

By 1937, the Great Purge, Stalin’s paranoid campaign of political repression, began to affect Krivitsky. The defection and subsequent assassination of his close friend Ignace Reiss served as a wake-up call. Realizing he could be the next target, Krivitsky decided to defect. He first fled to France and then to the United States. Krivitsky described himself as a "political corpse," having lost his faith in the Soviet system.

Flight from the Soviet Union: Krivitsky was recalled to Moscow and used the opportunity to "find out at firsthand what was going on in the Soviet Union". He concluded that Stalin had lost the support of most of the Soviet Union, including the army, commissars, factory directors, and the Party machine. Krivitsky was deeply concerned about his safety, especially after the execution of Theodore Maly, who had refused an order to kill him.

Collaboration with Paul Wohl: After deciding to defect, Krivitsky began to collaborate with Paul Wohl, a journalist, on literary projects. Wohl helped Krivitsky to connect with the French Socialist Party and obtain French papers and a police guard. They planned to move to the United States, where they would write about the Soviet Union. Krivitsky, his wife, and their son were initially refused entry into the United States and were held on Ellis Island until David Shub intervened.

Exposing Soviet Secrets: Krivitsky became a vocal critic of Stalin, exposing the inner workings of Soviet intelligence. He wrote a memoir, In Stalin’s Secret Service, which detailed his experiences as a Soviet spy. The book appeared initially as a series of articles in the Saturday Evening Post and was subsequently issued in book form. His first articles, especially the one predicting a Nazi-Soviet rapprochement, drew fierce criticism from communist and pro-Soviet publications.

Testimony Before Dies Committee: Krivitsky testified before the House Committee on Un-American Activities (HUAC), sharing his knowledge of Soviet espionage activities. He warned against the threat posed by the Soviet Union and accused Stalin of using France and Great Britain as pawns in his dealings with Hitler. His testimony before the Dies Committee contributed to the growing awareness of Soviet espionage in the United States.

Collaboration with British Intelligence: Krivitsky traveled to Great Britain, where he provided information that led to the arrest of several fifth columnists. He also provided intelligence that was used by MI5, although some of his information about Soviet agents in Britain was vague. Some argue that Krivitsky provided clues to the identity of Donald Maclean and Kim Philby, although the matter is still controversial.

Conflicts and Controversies

Krivitsky's defection and activism generated significant controversy. He faced accusations of being a fraud, a literary fabrication, and even a tool of anti-Soviet forces.

Accusations and Smears: The communist press attacked Krivitsky, calling him an impostor and claiming he was an anti-Semite. They also dismissed his writings as ghostwritten by Isaac Don Levine. These attacks aimed to discredit Krivitsky and undermine his influence.

Dispute with Paul Wohl: Krivitsky had a dispute with his collaborator, Paul Wohl, over finances. Wohl felt he was not adequately compensated for his work, leading to a lawsuit, which was eventually settled out of court.

FBI Skepticism: Although the FBI interviewed Krivitsky, they were skeptical of his claims and methods. They were concerned about his tendency to present his conclusions as facts and his association with Louis Waldman, a well-known socialist.

The Enigmatic Death of Walter Krivitsky

On February 10, 1941, Krivitsky was found dead in his room at the Bellevue Hotel in Washington, D.C., with a bullet wound to his right temple and a .38 caliber revolver nearby. The Washington police ruled his death a suicide. However, his wife, associates, and many others familiar with Soviet espionage believed he was murdered by the NKVD.

Suicide Verdict: The police based their conclusion on several pieces of evidence: the room door and window were locked from the inside; the gun was found near his right hand; three suicide notes in different languages matched his handwriting; and an associate claimed Krivitsky had expressed thoughts of suicide.

Challenges to the Suicide Verdict: Many contested the suicide ruling, citing numerous inconsistencies and suspicious circumstances. These included:

The room was cleaned before it could be properly examined.

The bullet was not recovered from the wall.

No fingerprints were taken from the doorknobs.

A paraffin test was not performed to detect powder residue on his hand.

Krivitsky had used his toothbrush and dental cream shortly before his death.

The absence of cigarette butts in the room despite Krivitsky being a chain smoker.

The suicide notes seemed unusually brief or unlikely given Krivitsky's relationships with the recipients, and contained postscripts which he never used.

The possibility the suicide notes were dictated.

The fact that Krivitsky was on the verge of becoming a naturalized American citizen.

His statements to others that he would never commit suicide, and that if he were found dead, they should know that he was "suicided".

The fact that Krivitsky had told Whittaker Chambers that, "Any fool can commit a murder, but it takes an artist to commit a good natural death".

Krivitsky's wife, Tanya Krivitsky, was certain that he "never would have killed himself willingly".

Theories of Assassination: Critics of the suicide verdict suggested that the NKVD had a motive to silence Krivitsky given his past revelations and possible future exposures of their agents. The fact that Krivitsky was a serious obstacle to Stalin's plans in the US was also cited. Some also believed the notes were forged by the NKVD.

Possible NKVD Operatives: Some suspected Hans Brusse of involvement in Krivitsky's death. Others pointed out that Brusse had been ordered to kill Elsa Poretsky, a mission he had sabotaged. Alexander Kerensky believed that Brusse, a known Soviet murderer, had driven Krivitsky to suicide by threatening his family.

Conflicting Testimony: Eitel Wolf Dobert, at whose farm Krivitsky had stayed prior to his death, claimed that Krivitsky was worried and likely committed suicide. This testimony contrasted with other accounts of Krivitsky's demeanor before his death, which was described as jolly and not despondent.

Speculation and Legacy: The circumstances surrounding Krivitsky's death remained a topic of speculation, with some arguing that Stalinist agents often made murders look like suicides. The inconsistencies and lack of a thorough investigation have fueled conspiracy theories. Some historians suggest that Krivitsky’s death may have been linked to the Soviet Union’s desire to eliminate a threat to their operations and to intimidate other potential defectors.

Conclusion

Walter Krivitsky’s life was a complex and contradictory journey through the turbulent landscape of 20th-century espionage. From his early revolutionary fervor to his disillusionment with Stalinism, Krivitsky's story offers valuable insights into the inner workings of Soviet intelligence and the personal costs of ideological conflict. His mastery of espionage tradecraft, his dramatic defection, and the circumstances of his death continue to intrigue and provoke debate, making him a significant figure in the history of the Cold War. He was a spy whose revelations shook the Soviet apparatus, a defector who couldn’t outrun the paranoia he once served, and a man whose greatest secret may have been whether he ever truly believed in the cause he so skillfully betrayed. His life serves as a sobering example of the perils of totalitarianism, ideological commitment, and the crushing weight of living with one foot in the shadows.