An Illegal in the Arctic

Mikhail Valerievich Mikushin AKA José Assis Giammaria

On an ordinary October morning in 2022, a self-proclaimed Brazilian academic named José Assis Giammaria strolled along a quiet, snow-dusted road in Tromsø, Norway, heading to his university office. He was, by all appearances, just another international researcher studying hybrid warfare and Arctic security—until Norway’s Police Security Service (PST) swept in and arrested him. Within days, the cheerful “Brazilian” with an interest in grey-zone conflicts was unmasked as something far more ominous: Mikhail Valerievich Mikushin, a 44-year-old colonel in Russia’s military intelligence agency (GRU) operating under deep cover.

A Spy in the Arctic – Arrest and Revelation

The arrest of “José Assis Giammaria” on October 24, 2022, sent ripples through Norway’s normally placid academic circles. The suspect had come to the Arctic University of Norway (Universitetet i Tromsø, UiT) in late 2021, attaching himself to a research group called “Grey Zone” that specialized in hybrid threats and warfare. He wasn’t even on the payroll – a volunteer guest researcher slot kept his footprint light and, he likely hoped, below the radar. Fluent in policy jargon and armed with a resume fit for a think tank, “Giammaria” blended in, focusing on Norway’s northern regions and security issues. His cover story cast him as a globe-trotting Brazilian scholar intrigued by Arctic geopolitics – a seemingly plausible persona in an era when emerging powers do show interest in the far north.

So when PST agents detained the bespectacled academic on his way to work, it came as a shock to colleagues. The university’s rector hastened to assure the public that no sensitive data appeared to have been stolen – though the real damage was to the institution’s credibility. Initial charges against the man were for entering Norway under false pretenses, but soon escalated to suspicion of illegal espionage “directed against state secrets” – a crime that can mean up to three years in prison under Norwegian law. As PST prosecutor Thomas Blom explained, the true risk was not stolen documents but the access the fake Brazilian had gained: embedding in research networks that inform national policy is itself “of significant national importance,” he noted. In other words, a spy doesn’t necessarily need to pilfer files if he can mingle with those who shape a country’s decisions.

The unraveling of Mikushin’s cover was swift. By that Friday, Norwegian authorities announced that the suspected “Brazilian” was almost certainly a Russian operative named Mikhail Mikushin, born in 1978. “We are quite certain that he is not Brazilian,” Blom deadpanned to the press. It was an understatement. In fact, evidence soon showed that Mikushin was a seasoned GRU officer of colonel rank, not some junior mole fresh out of spy school. “Great job, Norway, you’ve caught yourself a colonel from the GRU,” crowed Bellingcat researcher Christo Grozev in a congratulatory tweet. Norwegian media reported this was the first ever known case of a Russian “illegal” intelligence officer caught on Norwegian soil – a milestone no one in Oslo’s security circles was celebrating, but a milestone nonetheless.

For over a year after his arrest, Mikushin maintained an enigmatic silence, sticking to his Brazilian alias and denying wrongdoing. But in December 2023, facing the cold reality of a courtroom in Oslo, he finally cracked. “José” gave way to Mikhail as the spy admitted in court that he had provided false information about his identity and was indeed a Russian citizen. According to his Norwegian defense lawyer, Mikushin acknowledged that he lied to immigration authorities when applying for residency, effectively confessing to the core of the case. It was a rare moment of truth in a career built on deception. After the admission, Norway contacted the Russian Embassy in hopes of official confirmation, but the embassy feigned ignorance, even denying knowledge of any such Russian citizen. (Moscow’s reflexive who, me? response was entirely expected – after all, admitting “yes, that’s our spy” isn’t standard practice in the espionage world.)

From Soviet Son to “Brazilian” Scholar – The Making of an Illegal

Mikhail Valerievich Mikushin’s journey from the Soviet Union to a sham life as “José Assis Giammaria” is a study in the GRU’s long-game strategy. Born on August 19, 1978 in Sverdlovsk (now Yekaterinburg, Russia), Mikushin came of age in the turbulent 1990s as the Soviet empire crumbled. By the mid-2000s, he was on a very different trajectory than most of his peers. According to investigative journalists, Mikushin graduated from the GRU’s elite military intelligence academy around 2006, emerging as a freshly minted officer of Russia’s shadowy spy service. At precisely the same time, he took an extraordinary step: he acquired a new citizenship and identity, Brazilian name and all. This wasn’t a casual bit of cosplay – it was the foundation of his legend, carefully sanctioned and likely facilitated by his spymasters in Moscow. Russian illegals often spend years building up a false persona, and Mikushin’s case was no exception. He reportedly claimed that his mother was Brazilian to justify obtaining Brazilian citizenship in 2006. Whether this involved stealing a real person’s identity or forging records is still murky. What’s clear is that from that moment, “Mikhail from Yekaterinburg” faded into the background, and “José from Brazil” was born.

Why Brazil? For Russian intelligence, far-flung countries like Brazil offer attractive cover. A Russian posing as, say, a Pole or German might attract more scrutiny in NATO circles than someone from a Latin American nation. Brazil in particular has unintentionally lent several of its identities to Russian spies in recent years – a macabre honor roll that includes the infamous “Maria Adela” who charmed her way into NATO’s Naples circles, and Sergey Cherkasov, who pretended to be a Brazilian student and nearly infiltrated the International Criminal Court. Brazil’s large population and less aggressive passport controls have made it a favorite wellspring for Russia’s deep-cover operatives. Mikushin’s adoption of a Brazilian persona fits this pattern. It gave him a non-Russian nationality, a plausible backstory far from Moscow, and access to countries (like Canada and Norway) with relatively friendly ties to Brazil. And importantly, Brazilian citizenship let him travel globally with far less suspicion than a Russian passport might arouse.

Before Mikushin ever set foot in Canada or Norway as “José,” he likely underwent extensive preparations. The GRU doesn’t just hand someone a fake passport and wish them boa sorte (good luck in Portuguese). Illegals typically spend years training: mastering the language (Mikushin would have needed to speak Portuguese convincingly, possibly with a dash of a Brazilian carioca or goiano accent), learning the history and culture of their assumed country, and rehearsing every detail of their fictitious childhood. By the time Mikushin left Russia around 2006 under his new alias, he had to genuinely become José Assis Giammaria in habits and memories. Indeed, Norwegian investigators later found that back in Moscow, Mikushin’s last listed residence was literally at a GRU facility – the kind of housing reserved for military intelligence personnel. That suggests his transformation into an “illegal” was no side hustle; it was his full-time occupation.

Interestingly, Mikushin did not sever all ties with Russia after 2006. Spy catchers discovered, for example, that he popped back into Russia in June 2015 to renew his Russian driver’s license. (Even deep-cover operatives apparently need to keep their driving privileges up to date – perhaps in case of a sudden exfiltration requiring a long road trip.) Such trips would have been delicate operations: “José” the Brazilian presumably could not waltz through Moscow’s Sheremetyevo Airport without awkward questions. It’s likely Mikushin traveled under his real identity for these brief returns, carefully timing them to avoid blowing his cover. Each visit back to Mother Russia carried risks, but also rewards – fresh instructions, training updates, and a chance for GRU handlers to ensure their man hadn’t “gone native” after years abroad.

Years in the Great White North – Building a Canadian Legend

If Mikushin’s new life began in 2006, its first act played out in Canada, of all places. By 2010, investigators believe, “José Assis Giammaria” had arrived in Canada to lay down roots. He spent the better part of the next decade there, meticulously layering his cover story with real academic accomplishments and community involvement. Canada, it turns out, is a favored stepping-stone for Russian illegals destined for bigger things. The country is friendly, multicultural, and far from Moscow – an ideal proving ground where a fake Brazilian could live openly, network, and even make a few mistakes out of view of European counterintelligence. One former GRU officer noted that illegals are often sent to such “stepping-off” locations first to consolidate their legends before moving on to their ultimate target. With its welcoming universities and diverse population, Canada offered Mikushin the perfect stage to solidify “José’s” identity.

Academia was Mikushin’s cover career, and he pursued it with genuine zeal. He enrolled at Carleton University in Ottawa, a well-regarded school, and by 2015 he had earned a Bachelor of Arts in Political Science with a concentration in International Relations (and a minor in Communications). Not only did this add bona fides to his alter ego, it also placed him in proximity to aspiring diplomats and policy wonks. (Carleton’s campus is known for the Norman Paterson School of International Affairs – exactly the kind of environment a budding spy might find useful contacts or insights.) Classmates and professors saw “José” as a dedicated student. Little did they know the term papers on Arctic geopolitics he was writing were part of a much longer game.

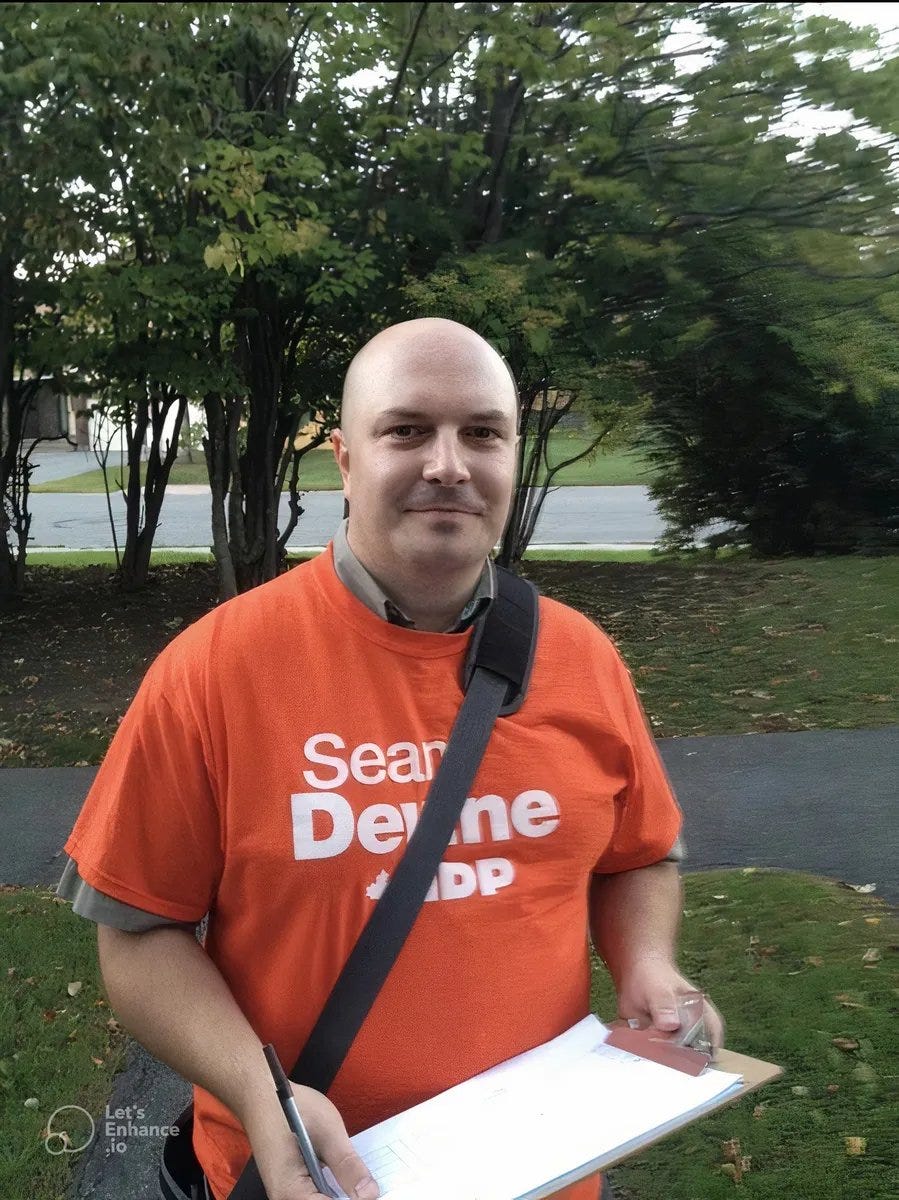

Mikhail Mikushin (under alias “José Assis Giammaria”) during his time in Canada, where he even volunteered in 2015 for a Canadian political campaign. In deep-cover operations, building a convincing personal history is as crucial as any espionage tradecraft.

Mikushin didn’t stop at one degree. He headed west to the University of Calgary, where he completed a Master’s in Strategic Studies in 2018. Calgary’s program, focusing on security and strategy, would have further deepened his knowledge of Western military and policy issues. By all accounts, “José Giammaria” was a diligent scholar – perhaps genuinely so. (One can imagine the peculiar situation of a GRU officer getting graded on a thesis about Arctic security by unsuspecting Canadian professors!) During this period, he began to zero in on the Arctic as his specialty, an area of obvious interest to Moscow. In fact, he even published an article in the respected Canadian Naval Review in 2019, writing under his alias. The piece argued that Canada should establish a permanent military base in the Arctic – advice that, intentionally or not, dovetailed with Russia’s strategic view of the High North. It’s a delicious irony: a Russian spy, hiding in Canada, urging Canadians to beef up Arctic defense. Was this simply academic musing, or was “José” trying to shape dialogue in ways subtly favorable to Russian interests? We don’t know, but it certainly burnished his credibility as a bona fide analyst of Arctic policy.

Beyond the classroom and journals, Mikushin worked to blend into Canadian society. In a particularly audacious move, he volunteered for a political campaign. In 2015, he served as an unpaid volunteer for an NDP (New Democratic Party) candidate in Nepean, Ontario during Canada’s federal election. This wasn’t a high-profile role (more likely door-knocking or data entry than speechwriting), but it speaks volumes about his methods. By volunteering, “José” demonstrated civic engagement – the kind of thing no one would expect a Russian operative to do, thereby defusing suspicion. It also gave him a chance to meet local politicians and activists, perhaps filing away tidbits on who’s who in Canadian politics. Canadian security expert Stephanie Carvin noted that Mikushin’s time in Canada was likely all about building his legend – the rich tapestry of documents, social media, friendships, and experiences that make a false identity real. Indeed, Canadian authorities later confirmed that nothing he did in Canada blatantly crossed legal lines. He didn’t try to steal state secrets there. His mission was quieter: become a real person. And in that, he largely succeeded.

By the late 2010s, Mikushin had amassed a treasure trove of what intelligence agencies call “legitimators”. He had two Canadian degrees, professional connections, and even co-authored scholarly work. He had Canadian friends and presumably a thick stack of selfies from Tim Hortons coffee shops and Niagara Falls – all the normal trappings of a life overseas. These years were an investment by the GRU, and Moscow expected a return. Russian illegals typically aren’t sent abroad just to sightsee and study; they are talent-spotters and access brokers. During his time in Canada, Mikushin likely kept an eye out for promising individuals who might later be valuable to Russia – people with potential access to government, tech, or military circles. Any friendly classmate who went on to join the Canadian civil service or a NATO-affiliated think tank could become an unwitting asset down the line. As one analysis noted, “the job of the illegals was to find those people” who had access to secrets or influence. We don’t know whom Mikushin might have identified or reported on, but one has to wonder if some of his friendly chats over coffee in Ottawa have since been scrutinized in hindsight.

By 2020, our “Brazilian” had spent a decade in the Great White North. If Canada was meant to be a springboard, the question was where he’d land next. The answer came into focus: Norway. With the world’s gaze turning to Arctic security, climate change opening new northern sea routes, and NATO sharpening its focus on the High North, Norway was a hotspot for exactly Mikushin’s area of expertise. Armed with his Canadian credentials (and no doubt glowing recommendation letters from Canadian professors who had no clue of his true identity), “José Assis Giammaria” applied for a position in Norway. And why wouldn’t he get it? He looked great on paper. Here was a trilingual (Portuguese-English possibly Norwegian-learning) PhD candidate-level researcher with niche expertise in hybrid warfare and Arctic policy – plus he was willing to work for free. For the University of Tromsø, it was an easy sell.

Arctic Ambitions – Infiltrating Norway’s Academia

In the fall of 2021, José Assis Giammaria arrived in Norway with the same low-key charm he likely wielded in Canada. He joined UiT (the Arctic University of Norway) as a visiting researcher under a program focused on hybrid threats. Tromsø, a small city above the Arctic Circle, suddenly had a “Brazilian” scholar in its midst, but nothing about Mikushin’s behavior raised alarms at first. He kept a low profile, reportedly working “for free with a research group” and integrating into the academic community. The research project he was part of – tellingly named Grey Zone – was examining those ambiguous tactics that fall between war and peace. If the GRU had wish-listed an ideal posting for their man, they couldn’t have done much better than embedding him among Western experts studying Russia’s own playground of hybrid warfare.

Mikushin’s timing, however, was less than ideal for a Russian spy trying to fly under the radar. In 2022, the world changed. Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February sent shockwaves through Europe – and jolted Norway’s sense of security. Suddenly, Russian spies and saboteurs were front-page news. By autumn 2022, Norwegian authorities were on high alert for anything fishy: mysterious drone sightings near strategic sites, Russians photographing military bases, you name it. In this charged atmosphere, a foreign researcher with an unusual background might have drawn a second glance from PST. Indeed, news later emerged that PST had been investigating “Giammaria” for some time before pouncing. It’s still unclear what exactly tipped them off. It could have been a tip from a foreign partner agency (perhaps Canada – though Canadian officials claimed they hadn’t suspected him while he was there). Or it could be that Mikushin slipped up in a small way. Ironically, the super-spy’s downfall may have been hastened by something as banal as reusing an email password. Investigative journalists from VG (Norway’s Verdens Gang newspaper) and Bellingcat uncovered that Mikushin had employed the same email address to apply for his Tromsø gig that he’d used elsewhere. That email and its password led them to accounts on Russian platforms and even a photo of Mikushin’s Russian driver’s license – smoking-gun evidence that José and Mikhail were one and the same.

Once PST had Mikushin in custody, the pieces fell into place quickly. A search of his lodgings and devices presumably yielded further confirmation (though details remain classified). Investigators even checked his registered addresses in Russia and found he was tied to a Moscow apartment complex notorious for housing GRU officers. In short, the meticulous legend built over 15+ years unraveled in mere days. One has to imagine Mikushin’s astonishment – after all that investment in living his legend, he was caught by what one insider termed “lousy operational security tradecraft” such as reusing credentials online. The best-trained spies are still human, and humans have habits; in a digital age, those can be exploited. It’s a poignant reminder that while cover legends can be elaborate, their downfall often hinges on a few small threads coming loose. Pull one thread – an email here, a travel record there – and the whole fabric can unravel.

Norwegian authorities, for their part, handled the case with a blend of firmness and legal prudence. Mikushin was initially charged under a relatively minor statute (using false identity) just to hold him, and then formally charged with espionage related to state secrets a few days later. The espionage charge was a first for an “illegal” in Norway, marking a new chapter in the country’s counterintelligence efforts. The fact that Mikushin’s mere presence under false identity was rolled into the charges underscores how seriously Norway viewed the breach. Even if he hadn’t stolen specific secrets, the very act of masquerading as Brazilian when he was Russian was criminal – a nuance one doesn’t often see spelled out in spy cases. Mikushin, of course, pleaded not guilty through his lawyer and maintained for a long time that it was all a misunderstanding. (One imagines his defense strategy had shades of: “I’m just an academic doing open research! What crime?”) Yet, as VG’s reporting and Bellingcat’s data digs tied up the loose ends, his position became untenable. By late 2023, cornered and likely hoping for a way out, Mikushin finally dropped the act and admitted who he was.

The Endgame – Exposure, Swap, and Reflections

What do you do with a caught Russian spy? In novels, the options range from dramatic (exchanges on fog-shrouded bridges) to grim (dank prison cells). Norway chose a mix of due process and pragmatism. Mikushin sat in a Norwegian jail for nearly two years awaiting a trial that was repeatedly postponed. There’s reason to believe the Norwegians themselves were in no rush to conduct a public trial that could expose sources and methods of how they caught him. By mid-2023, rumors swirled that Mikushin might become a pawn in a larger East-West negotiation. Indeed, Norwegian officials quietly acknowledged to media that the Russian was being considered for a potential prisoner swap involving Western detainees held by Moscow.

Sure enough, in a dramatic turn of events in August 2024, that’s exactly what happened. Mikhail Mikushin was part of a major multi-national prisoner exchange between Russia and the West. Norway’s Prime Minister Jonas Gahr Støre confirmed that Norway contributed to the exchange, which freed a number of Russian political prisoners and Western citizens from Russian custody. In exchange, Russia got back several individuals arrested in the West – Mikushin among them. It was described as the largest East-West prisoner swap in recent memory, involving 21 people by some counts. The trade included high-profile names like American journalist Evan Gershkovich and Russian opposition figures such as Vladimir Kara-Murza. Tucked in that roster was the mild-mannered “researcher” from Tromsø who had been unmasked as a GRU colonel. In essence, Norway handed Mikushin back to Moscow rather than continuing to hold or prosecute him – likely a calculated decision to win freedom for innocents held by Russia.

For Mikushin, it meant an abrupt homecoming. One day he was an accused spy in an Oslo jail; a day later, he was a free man in Russia (though “free” under Putin’s gaze comes with its own irony). Russian media, after long ignoring the case, trumpeted his return as part of a “big exchange”, conveniently glossing over what he was doing in Norway in the first place. An article in Argumenty i Fakty even posed the question “Who is Mikhail Mikushin, and why was he arrested in Norway?” – a gentle way of reintroducing him to a domestic audience now that he was back in the fold. The official narrative in Russia has been predictably muted: they neither admit he’s a spy nor dwell on his Brazilian escapade. Meanwhile, Norway’s security service likely extracted whatever debrief they could from Mikushin before he left, adding to their understanding of how Russia’s clandestine “illegals” operate.

What does this saga tell us? For one, it pulls the curtain back on the GRU’s clandestine “illegals” program, showing both its ambition and its vulnerabilities. Mikushin’s trajectory was textbook in many ways: an officer trained and then “lost” to the Motherland for nearly two decades while he lived under a false flag. At any given time, Russia only employs a few dozen of these illegals worldwide, making them a relatively scarce asset compared to the legions of overt diplomats-cum-spies. Each one represents an immense investment. Mikushin’s cover took years of patient work – enrolling in schools, building friendships, even learning to barbecue on Canada Day, perhaps. All that just to position one intelligence officer close to Western Arctic experts. To the GRU, it must have seemed worth it. The Arctic is critical to Russia’s security and economic future; having a mole in those circles could provide early warning of Western plans or opportunities to subtly influence debates. As a talent-spotter, Mikushin could identify up-and-coming Arctic scientists or officials and report their details to Moscow for possible cultivation. As an ear on the ground, he could feed the GRU valuable open-source insights with an insider’s context.

Yet, for all that careful preparation, illegals are not superhuman. Mikushin’s uncovering shows how the classic cat-and-mouse game of counterintelligence continues in the digital age. The very tools that helped him assume a new identity – the internet, social media, academic CVs – also created a trail that clever investigators could follow. When VG and Bellingcat, essentially using open sources and data analysis, can crack a spy’s alias in a matter of days, it raises hard questions about the future of such operations. Mikushin was by no means the only one: as mentioned, just months before his arrest, Dutch intelligence exposed another Russian illegal who had posed as a Brazilian (Sergey Cherkasov) trying to infiltrate the International Criminal Court. And earlier in 2022, authorities in Greece and Brazil uncovered a married pair of deep-cover spies (one of them using a Brazilian business cover). It seems the Kremlin has been leaning heavily on the “Brazilian” playbook – so much so that one commentator wryly suggested they might want to diversify their legend portfolio. Using the same formula repeatedly is a good way to get burned, as these arrests demonstrate.

For Norway, the case was a wake-up call that even the high north isn’t immune to cloak-and-dagger intrusions. The country has since tightened security around its academic institutions and critical infrastructure. Norwegian counterintelligence has also had to contend with a rash of other Russian covert activities, from drone flights to suspicious land purchases near military bases. Mikushin’s exposure probably sharpened their vigilance; it’s not every day you catch a GRU colonel playing professor on your turf. As Norway’s PST chief Inger Haugland noted, Russian espionage can take ingenious forms – whether it’s illegals like Mikushin or seemingly innocuous business investments that provide cover for intelligence gathering.

And what of Mikushin now? Back in Russia, one imagines he’s being debriefed extensively by the GRU about what went wrong. There may be blame cast – perhaps unfairly – on him for the failure of the mission. (Spy agencies are not known for their gentle HR policies.) But he also returns as something of a quiet hero in the eyes of his service: he kept his lips sealed for as long as it mattered, revealed nothing of substance to the enemy, and has come home in one piece. The fact that Moscow wanted him back enough to include him in a high-profile swap speaks to his value. In a grim sort of way, Mikushin fulfilled his duty – he occupied Western counterintelligence and caused a diplomatic situation, becoming a bargaining chip for Russia to recover more important assets.

A Timeline of Mikhail Mikushin’s Journey from GRU Cadet to Captured “Brazilian”

Timeline: Key milestones in Mikushin’s covert career, from his 1978 birth and 2006 adoption of a Brazilian identity, through his years in Canada, to his 2022 arrest in Norway and 2024 return to Russia. Each step highlights the long-term investment and eventual exposure of his deep-cover mission.

Looking at the broad sweep of this case, there’s an almost old-fashioned quality to Mikushin’s saga – a 21st-century echo of Cold War tales. He wasn’t stealing nuclear codes or bugging embassies; he was studying and socializing, living the slow-burn life of an academic. His weapons were conference name badges and library cards, not microdots and poison umbrellas. It’s a reminder that modern espionage isn’t all high-tech hacking and cyber warfare. The humblest “grad student” might turn out to be an agent in deep cover, patiently gathering bits of intelligence the old-fashioned way – by earning trust. As one NATO official quipped to The Guardian, “Man posing as Brazilian academic… thought to have used his time [in Canada] to build up a deep-cover identity”. That about sums it up: Mikushin’s Canadian sojourn and Norwegian adventure were the careful brushstrokes of a portrait that was never supposed to be noticed as a fake.

In the end, Mikushin’s story is equal parts cautionary tale and dark comedy. Cautionary, for Western institutions, about the need to vet even the most benign-seeming visitors. (The University of Tromsø surely wishes it had asked a few more questions about its volunteer from Brazil.) Darkly comic, in that a highly trained Russian spy spent years becoming a genuine expert in Arctic policy – only to be outed and exchanged, his insights perhaps now of little use to anyone. One can’t help but picture Mikushin in some Moscow flat, reflecting wryly on the twist of fate: he devoted half his life to not being himself, only to have his true identity splashed across headlines.

As the dust settles, Mikhail Mikushin’s Arctic escapade will likely enter intelligence lore as a case study in the strengths and pitfalls of deep-cover espionage. It underscores that while you can borrow someone else’s name, history and even nationality, you can’t escape the watchful eye of counterintelligence forever – especially if you leave a digital trail. The GRU’s illegals program will no doubt adapt and continue; there will be other “Brazilians” popping up in unexpected places. But each time one is unmasked, it becomes a little harder for the next to succeed.

For Norway and its allies, catching Mikushin was a victory that combined sharp investigative work with a bit of luck. For Mikushin, getting caught was perhaps the only failure in an operation that, until that moment, had gone eerily well. And for the rest of us, his story offers a rare glimpse into a shadowy world – where a man can earn a degree, make friends, and even cheer for a political candidate, all in service of a lie. It’s a world where truth really is stranger than fiction, and where sometimes the Brazilian professor next door is secretly working for the Kremlin.

Sources:

Norwegian Police Security Service and court filings (via VG, PST press statements)

Investigative journalism by Verdens Gang (Norway) and Bellingcat

The Guardian (Oct 28, 2022); Associated Press via CBS News; Reuters via intelNews

The Insider (Russia) report by C. Grozev & M. Weiss (Dec 2023); O Globo (Brazilian newspaper); Interia (Polish news)

Policy Options (Dec 2022) analysis by G. Corneau-Tremblay; Barents Observer (Oct 29, 2022 & Aug 1, 2024); Anadolu Agency (Dec 2023) via AA.com.tr.